Before I learned to read neumes or chant notation, I couldn’t sight-sing at all and basically depended entirely on a keyboard to learn how to sing new tunes. Now I can sight-read from chant notation and, by extension, my sight-singing of modern notation has improved a lot. Here’s a quick introduction, which won’t teach you all the signs, but will get you started with the most frequent ones.

If you already know basic music theory, you can probably skip this section.

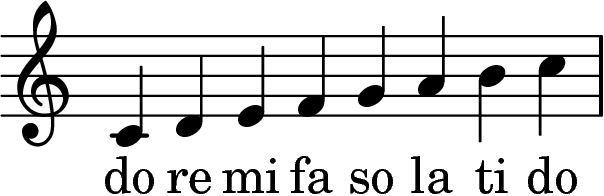

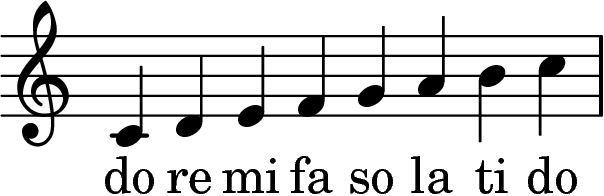

Everyone knows the basic musical scale: do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do. Sing it! In modern music notation we can write it like this:

This simple scale is the basis of plainchant. All the melodies of plainchant are created by just re-arranging the notes of this simple scale into different orders. Unlike modern music notation, there are no notes A to G, no sharps and flats or major and minor. (There are eight ‘modes’, but those are only of importance to people who want to write chant, rather than just sing melodies that have already been written.)

One thing it’s important to notice is that not all the steps between adjacent notes in this scale are the same. If you sing the step between re and mi and the step between mi and fa several times, you’ll notice that the difference in pitch is smaller between mi and fa than it is between re and me. The same is true of the difference between ti and do, compare to la and ti.

The musical scale of eight notes is not divided into seven equal steps, but into five ‘big steps’ (do–re, re–mi, fa–so, so–la, la–ti) and two ‘little steps’ (mi–fa, ti–do). If it were possible to add two ‘little steps’ together (it is possible in modern music notation, but not in chant), they’d make one big step. So the big steps are called whole-steps or whole tones and the little steps are called half-steps or semitones.

This means that when we have two notes written next to one another in notation, in order to work out what the right size of step to sing is, we need to know which lines and spaces on the staff correspond to the half-steps, and which correspond to the whole-steps.

To work this out, chant notation gives us two symbols called clefs. One of them is written one of the lines of the staff on every new line of chant notation. One is called the do clef and is written on the line where do is, and the other is called the fa clef and is written … well, on the line where fa is.

You might be able to remember which way around these are because the do clef is also the C clef (it’s the historical ancestor of the alto clef used by viola players) and the fa clef is the F clef (and the ancestor of the bass clef in modern notation), and they look like a C and kind of like an F.

Each line and space counting up or down from the line the clef is written on is a step in the scale, relative to those notes. Common to both clefs is that there’s a half-step between them and the note written in the space below them; where they differ is in the number of whole-steps below that note until the next half-step, and in the number of whole-steps above the clef until the next half-step.

For a practical example, let’s consider the opening of one of the most famous melodies in the Gregorian chant repertoire: Dies irae from the Requiem mass. This short figure has been quoted in numerous other works of music.

The do clef is written on the top line of the staff, meaning we need to count lines and spaces down the staff to know where all the other notes are:

Placing them side-by-side like this makes it obvious that the first note of the melody is fa, and thinking back to our discussion of whole-steps and half-steps, we know that there’s a half-step between the top line of the staff and the space below it (do and ti), and between the second line from the bottom and the space below it (fa and mi).

Sing ‘do, re, mi, fa’. Stop on fa and go back down to mi, then back to fa. Repeat this, but after you go back to the fa, continue back down to re, skipping over mi entirely. You’re singing Dies irae! See if you can add the rest of the notes yourself.

Now let’s consider a tune you might not be familiar with: the ending of one of the Gregorian psalm tones.

As before, the clef is on the top line of the staff, but this time we start on this top do, and not on fa. (Note that this doesn’t mean you have to sing it any higher at all: all pitch in plainchant is relative, not absolute — i.e. what matters is the relations between half-steps and whole-steps, not any particular pitch you start on.) When singing this, you might find it helpful to start by singing the scale backwards down to so (do, ti, la, so) and then try and sing the notes in the correct order as written.

In both of these tunes we’ve had cases where we’ve had to skip over multiple steps in the scale from one note to another: in ‘irae’ in the first example, and in ‘world without’ in the second. If you count the whole- and half-steps in such leaps, you can use this handy table to find an approximate reference.

| Steps | Example | Modern musical name | Think about … |

|---|---|---|---|

| ½ | do–ti | Semitone | The first two notes of Für Elise |

| 1 | do–re | Tone/Whole tone | First two notes of the scale |

| 1½ | do–la | Minor third | Bird singing ‘cuckoo’ |

| 2 | do–mi | Major third | First two notes of ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’ |

| 2½ | Perfect fourth | Second and third notes of the theme to 2001: A Space Odyssey | |

| 3 | fa–ti | Augmented fourth/diminished fifth | The opening notes of ‘Purple Haze’* |

| 3½ | do–so | Perfect fifth | First two notes of the theme to 2001: A Space Odyssey |

If you consider each line or space on the staff a to be ‘position’, and count steps including both the start and the end note, then a difference of two positions will always be either a half-step or whole step; a difference of three positions will be either a minor third (if there’s a half step within the lines and spaced between those positions) or a major third (otherwise); and a difference of four positions will almost always be a perfect fourth, and a difference of five positions will always be a perfect fifth.

Leaps larger than a perfect fifth are quite rare in chant. If you need to make one, it’s probably easiest to break it down into multiple steps for yourself in your head, then only sing the start and end notes.

In order to sight-sing any music, including Gregorian chant, you will need a good sense of ‘relative pitch’. That is, you have to be able to sing and recognize differences of a semitone, tone, third, fourth, and fifth immediately ‘by ear’ without any reference. You can learn good relative pitch in a weekend or so, but everyone will prefer a different method — Google has quite a lot of suggestions.

Here’s one last practical example that’s just a tiny bit trickier before we move on to some other details of the notation. This one is the beginning of the Sanctus from John Merbecke’s setting of the Anglican communion service (1549).

Here we have our first use of the fa clef, but we actually still start on do and continue by going up the first three notes of the scale. Try it!

A distinctive feature of advanced Gregorian chant is its tendency to sing lots and lots of notes to the same syllable. An instance of this is called a melisma (plural melismata). Chant notation writes it roughly as you’d expect, by writing multiple square notes above a single syllable, but there are a few nuances.

As a basic principle, Gregorian chant follows the same rule as modern notation: a note that appears to the right of another note is sung after it. For instance, as you’d expect, there are melismata from mi to re on ‘out’ and from fa to me on ‘end’ in this psalm tone ending:

However, mediaeval monks were short on space on their expensive vellum pages so they had some abbreviations which continue in modern use. For melismata going upwards the second note is written directly above the first one () — but upwards melismata of more than two notes will still be written with some of the notes next to each other instead of directly on top. Here’s the alleluia at the opening responses of the office (also showing the do clef on the third line from the bottom, instead of on the top line):

In this case we have a melisma from do to re on ‘le’, and another from do to ti on ‘ia’.

Melismata which go down and then back up again are written rather differently, with a single thick swooshy line between the first and second notes, then the last note written above the end of this swoosh. The swoosh does not mean to glide or glissando from the first to the second note! In this ‘Amen’ from the end of an office hymn, the second syllable goes (cleanly) from so to fa, and back to so.

In some melismata you might see that some notes are written with a diamond note () instead of a square one (

). There is no difference between diamond and square notes, but a diamond note will never appear on its own — it always belongs to the same syllable as the last square note that appeared before it. (This is important e.g. when reading notation which is separated from some (pointed or metrical) text printed separately.)

With all this in mind, here’s a much more complicated melisma. Have a go at singing it, but don’t worry if you can’t get it, or if it takes you a lot longer than the other ones. Long melismata can be very daunting!

At the beginning of this guide I wrote:

All the melodies of plainchant are created by just re-arranging the notes of this simple scale into different orders. Unlike modern music notation, there are no notes A to G, no sharps and flats or major and minor.

Now I have to confess: this is a lie. I know, very un-Christian, sinful, etc. — I’ll be confessing it on Sunday. In my defence, it is only a small lie, and a pedagogical one at that, since I didn’t want to overcomplicate things in the beginning.

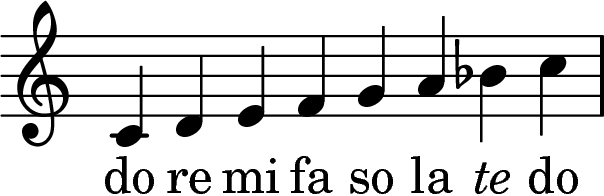

There is one flat which can appear in chant: the B-flat or ‘te’, which replaces ‘ti’ in the scale when it appears. (‘Te’ rhymes with ‘re’, as ‘ti’ rhymes with ‘mi’.)

The difference between la and te is a half-step, and the difference between te and do is a whole-step. In other words, a do–re–mi scale with a te or ‘B flat’ is the same as singing all the notes of the scale, but starting and ending on so instead of do. (Don’t worry if that wasn’t obvious — all that matters is understanding that the whole-step and half-step at the top of the scale are swapped around.)

The flat sign in chant notation looks basically the same as in the modern notation above. It can appear in two positions: one right next to the C clef, which means that all ti notes in the whole chant are chanted to te; and one immediately before the written note ti, in which case only that single note ti is changed. In other words, the following two are musically identical:

Informally, for reading purposes, you can think of the do clef with this flat sign as being the ‘so clef’, although it’s not formally called that.

In modern performance, only a handful of rhythmic features are considered musically significant in plainchant. Other than those, the beat is either identical to speech rhythm (where longer passages are recited on a single note) or with equal time on each note.

One way rhythm is indicated is by writing the same note for the same syllable twice in a row. As you might expect, that means you spend about double the amount of time on that note compared to others. We saw this above in the second ‘Alleluia’ example.

In this example, we should spend about double the amount of time on the ‘dore’ in ‘adore’ than on the ‘a’ or on the ‘O’ at the beginning. This also shows another rhythmic symbol, the dotted note. Just like in modern musical notation, this means to extend the length of the note, but without quite doubling it. In practice, the dotted note is usually found at the end of sentences where you’d be about to take a pause for breath anyway.

There are other rhythmic signs such as the episema which is a line placed above or below some notes, also having a lengthening or emphasizing effect, and the quilisma, a wavy note () in a melisma which is sung short, with the previous note sung longer to compensate (like a dotted rhythm in modern notation) — but you don’t really need to know about those to perform plainchant reasonably well as a beginner or in a congregation.

See if you can read these short snippets from the Gregorian chant repertoire. Some of them are quite famous, others more obscure.

The standard work for English plainchant is Briggs and Frere’s Manual of Plainsong. In its original form it used a non-standard simplified notation, but fortunately David Stone has recreated it in standard plainchant notation which is useful for practicing reading the notation. It has all the psalms written out in full (no pointing on the text!) as well as the canticles for morning and evening prayer and other bits from the Anglican prayer book. A good way to get initial practice is to use Stone’s version of the psalter to chant the psalms to yourself when praying morning or evening prayer privately at home. (As St Augustine didn’t say, qui cantat bis orat — whoever sings prays twice!) When you get more experienced you can start singing the ‘solemn’ forms of the Magnificat and Benedictus (one of them is printed above in Latin), which were used on feast days while the simpler forms were used on ferias.

The old (pre-Vatican II) standard work of Latin plainchant was the Liber usualis, which you can download in PDF format with English rubrics from the website ‘Corpus Christi Watershed’. It also explains all the signs used in chant notation in the foreword, including the ones I didn’t cover here.

An amazing resource currently in progress is the Sarum Rite edited by William Renwick. Rubrically speaking, it’s a nightmare to get your head around, but when he’s done we’ll have probably the largest single repository of English plainchant in the world.